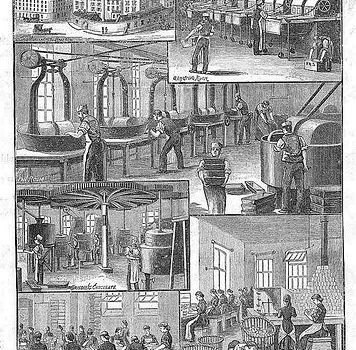

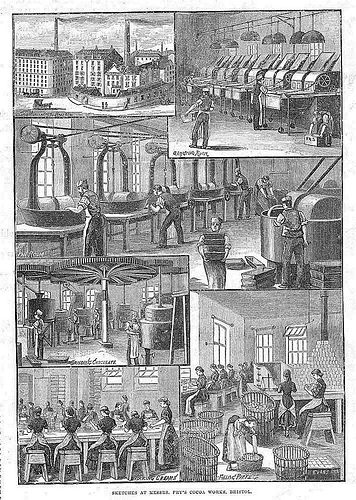

1884 Factory Tour of Fry’s Chocolate Bristol

Image by brizzle born and bred

Anybody who passes along Wine Street, Bristol, will, if he be keen-scented, grow to be totally aware that he is close vicinity of a chocolate factory. The aromatic berry scatters its perfume far and wide.

The manufacture itself is a growth of a century and a half. The first patent, still in the possession of its present companies, is dated 1730, and the old creating where the chocolate was then created, though solid and handsome, stands in vivid contrast to the huge pile of buildings which pour forth the chocolate and cocoa at the rate of a number of tons per day.

Any 1 getting into the factory can not but be impressed with the ceaseless whirl of machinery, the common sense of movement, and the continuous activity that pervade the buildings.

Here is a massive wheel, several feet in diameter, driving a series of grindstones which are pulverizing the nut there is a winnowing machine, which separates the husks close by is an elevator, which lifts the nibs to their subsequent position and so on all through the entire developing — machinery carrying out the function of hand labour, rendering food cheaper, and but obtaining employment for the bigger quantity of workers.

In the factory itself, you thread your way by means of walls of solid chocolate which appears like red granite blocks prepared for a new building instantly contiguous are other people of comparable shape and size, not in contrast to blocks of Portland Stone.

The last are composed of the solidified fat yielded of the cocoa berry in the approach of forming extract of cocoa.

Flanked on either side and piled up to the ceiling are the mountains of the bags containing the cocoa as imported into this nation. On the top floor of the developing the method of manufacture begins exactly where the nuts are roasted in enormous cylindrical roasters, constantly revolving more than a hot fire, and every single cylinder containing about a hundredweight of cocoa beans.

When cooked, the berries are cast into what is technically identified as a hopper — that is, a wooden partition about six feet square, in the center of which is a hole in the slate flooring, and through which the roasted cocoa beans are constantly descending by a conduit to the floor below. Subsequently the husks are separated from the bean itself by a really ingenious through basic arrangement.

The cocoa beans are made to pass in between two quite tiny rollers, which are about a quarter of an inch apart, and on the surface of each and every roller are tiny knife like projections, which break the husk but do not crush the nibs they then pass into the winnowing machine, by the elevators, into the mills, exactly where the beans are crushed into chocolate by, revolving drum, stone mills, or steel roller, until at length it problems, in continuous streams, a rich, fragrant, and deliciously brown liquid.

There is at this point of the manufacture two distinct processes, completely different in their aim: the one particular, the production of cocoa extract the other, the production of Perl and Caracas Cocoa. Cocoa extract is produced by extracting a large proportion of fat from the cocoa.

The mode in which this is effected is not a little singular. The cocoa is place into strong canvas bags, and from its basic appearance which hence manipulated is visibly suggestive of dynamite. These bags are composed of really robust double-sewn canvas.

They are placed into a hollow iron cylinder, the bottom of which moves up by hydraulic power of 1,200 lbs to the square inch, with the result that the fat drops into troughs, and when cool forms those Portland Stone blocks to which we have previously referred.

Whilst the fat is cooling in the troughs, the steel rollers are whirling round, crushing the ordinary nibs and incorporating the sugar, whilst completely manipulating the entire, and shredding into fine delicate flakes that planet-famed Caracas Cocoa.

1 is tempted to pause by the mill and taste as soon as again the luxurious compound of excellent cocoa, sugar, and vanilla.

We English have scarcely reached the point of appreciating how charming a luncheon is afforded by a stick of chocolate and a hunch of fine white bread. In other parts of the performs are small lakes of sugar getting converted into snow-flake, and chocolate being moulded into drops and bonbons.

At other parts there are steam-planes, steam-saws, and other machinery making wood boxes and finishing them with a rapidity that is really marvelous.

In one particular shop there are tin-workers who stamp out the lid, place on the finish, and present you with a completely tight tin canister in anything significantly less than a minute. Everywhere there is pressure, movement, and order.

The nimble fingers that affix the labels to the packets, equally with these that fill the packets themselves, weary the eyes by the rapidity of their movement. Enormous instances travel to and fro, as they pass to one or yet another of the wonderful packing departments, while trollies, laden to the utmost, carry boxes and packages to be sorted out and sent to every single part of England and each quarter of the globe.

A century and a half of constant and ever escalating effort lives in the factory, and those who right now listen to their of cautiously planned machinery can’t fail to don’t forget these early instances when chocolate was the luxury of the wealthy instead of getting, as it is to-day, the everyday necessity of millions of our people.